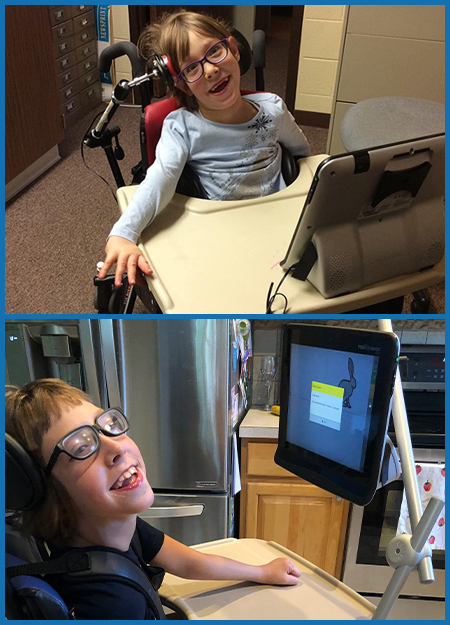

AAC devices enable communication for those with multiple disabilities.

AAC devices enable communication for those with multiple disabilities.

Augmentative & Alternative Communication, more commonly called AAC, consists of high tech (dynamic in that they speak what the individual wants to say) and low tech (static, as they do have the speak function).

Examples of high-tech items are devices, such as iPads and dedicated computers.

Low-tech items are core boards, communication books (the Pragmatic Organization Dynamic Display or PODD books are one), individual pictures, and so on.

Assistive Technology is available for those with multiple disabilities to access high-tech devices. These can include a mount on the wheelchair to keep the device close at all times, a keyguard to assist in the accurate selection of the words the individual wants to say, or switch access that the individual can press in any consistent way, even eye-gaze technology.

All these devices allow the individual to look at the words that they want to say for activation!

AAC uses two types of vocabulary.

With simple vocabulary, we use a few pictures (icons) that traditionally represent things (nouns) in the individual’s environment.

A robust vocabulary includes the noun icons but is predominately “Core” based. Core Vocabulary is reusable, generic words, such as pronouns, verbs, descriptions, negatives, parts of speech, and questions.

Robust vocabulary software also provides: ready-made phrases for those used most often, categorization of fringe vocabulary to help find the item wanted, navigation tools to lead to other pages rather than having a vast number of icons on one page, and some have options to allow the individual to control their environment (lights on/off) with the device. There are many choices of robust vocabulary available.

There are three different symbols sets that are used most often for the pictures. A few of these are Board Maker Symbols (Mayer-Johnson), Symbol Stix, Pixon (Semantic Compaction), Bliss, and PicSyms.

Learning to communicate begins with core vocabulary.

Learning to communicate begins with core vocabulary.

Core Vocabulary is 20% of the words people use 80% of the time.

The opposite of Core is Fringe Vocabulary, or proper nouns. Fringe Vocabulary is 80% of the words available to people and are used 20% of the time.

When children begin to talk, they use a few nouns that are important to them at first. Most of the time, these words become their Personal Core. Then, core words enter the picture to combine words with being more specific in what they say.

Since birth (likely in the womb), children learn language by hearing words spoken either around them or to them. It makes sense that their first sentences would imitate those they hear, which average 80% core and 20% fringe. So, why not teach those who are not communicating in the same way?

AAC has evolved immensely over the past decade. With the introduction of Core Vocabulary, both for speakers and non-speakers, the expressive outcomes of AAC users grow faster than the traditional AAC teaching approaches.

But how do we teach them to do this?

You, as parents, are the best communication partners your child has. When the communication partner uses proven strategies to communicate with their child, wherever they may be (e.g., during the day-to-day routines), the child learns to communicate most effectively.

The reason is because parents typically say and do the same things during routines, whether it be a bath or going away in the car. I use and teach these strategies to parents as a significant part of therapy.

Another thing to keep in mind is that using AAC relies predominately on ‘motor memory’ and not picture/icon discrimination. Motor memory is what we use when we turn on the stereo or wipers in the car. When you drive someone else’s car, the buttons are where your motor memory thinks they are. It’s the same with using AAC. The icons remain in the same place, and the individual learns that and relies on it.

Remember that using AAC is like learning a language.

Remember that using AAC is like learning a language.

The first thing I point out to parents and other communication partners is that learning to use AAC is like learning another language.

For individuals with complex and severe communication difficulties, speaking like their family is not an option. We talk to them in their native language, but they cannot reciprocate the same way. A child learning to use sign language is an example of someone who needs to learn how to use language differently than speakers.

So, we bridge the gap by using the same method as they are learning to do – the AAC device. What we model (say) on the device is what the individual states. It’s a match! When you speak to your child using AAC in everyday conversation, you use the AAC device. It’s not easy at first to use, that’s for sure! However, it does a couple of things for the individual – it forces us to slow down our speaking rate and pare down what we say to them.

One needs to think ahead a bit ahead to decide what are the most meaningful words you want to say. Do you want to know if they want something? Ask “what want?” using the device. Do you think you know what they want already? Then, you should ask, “you want item name?” speaking the item name but using the device for ‘you want.’

Remember the information shared earlier about core vocabulary used 80% of the time to talk. Start there. Most robust vocabularies have the first page as 80% core vocabulary.

Learn to wait for a response to your statement.

The next most important thing I teach parents is to use “wait time.” That means after you speak on the device, you give the individual time to communicate back. Stop talking!

Remember, the language is new to them, and just because they understand what you say and what you’ve modeled doesn’t mean it comes automatically. Give it time to be thought through and a response created, as well as how to do that on the device.

Speaking is so automatic that we forget that it is not intuitive for AAC users initially.

Learn to follow the individual’s lead.

Another technique is to “follow their lead.” I learned this years ago from the great people at the Hanen Centre in Toronto, Canada. Observe their behaviors – frowning, smiling, looking at something, inappropriate behavior – and give them the words for what you see using the device. For example, if the individual is acting out, screaming, rocking in the wheelchair, etc., you say, “you mad” on the device. Follow it by saying, “you not want?”

Once the individual knows you received the message, the behavior may subside – not right away. But over time, the individual feels heard and begins to sense a different way to control the situation.

Behavior is communication, so make communication the behavior! If you know what they want, then say, “you want item name? as mentioned above. I give the individual the item (if possible) because it demonstrates the appropriate way to get what one wants! If the request is not possible, you state why it’s not available “no more item name” and show them that this is true. Again, the individual feels heard and begins to sense a different way to control the situation.

When the individual gains ability to use the device with or respond to your modeling, I expand by adding a word or two on the device to what was said. For example, “I not want” was spoken on the device. I say, “you not want that.” The word that is marvelous for things that are within sight. I can point to it when I activate the picture on the device and help the individual point to it. If you are not able to point, I ask them to look at the picture. These gestural behaviors are important in nonverbal communication skills.

Expand beyond the core language.

Fringe vocabulary (nouns) are added in to allow the communication to be more specific. Remember the ratio of 80% core to 20% fringe here. Instead of saying “you want that” (all core) now say “you want ball” (core/fringe). This is the time to use personal core/fringe such as a favorite toy, food, or places to go.

From here, it is all expansion based on traditional language therapy, including word-combining for more specific communication, fringe vocabulary, and describers to create sentences.

Then, we introduce parts of speech for even more specific communication. These parts of speech include: when (now, past, or future), how many (one versus many), or whose (his, hers, ours, yours). We teach these in the sequence that we know children learn language.

Happy communicating!